Quatre Théâtres d’opérations sont créés à la mobilisation de septembre 1939 dont le Théâtre d’Opération du Sud-Est (TOSE).

The army of the Alps

This TOSE, under the command of General Billotte, comprised 600,000 men, but the 6th army under the command of General Besson was its main backbone. It was made up of 3 army corps (CA), with a total of 550,000 men.

On September 1, the Italian government proclaimed its non-belligerence, which meant that for the time being Italy would not enter the conflict but would reserve its position for the future.

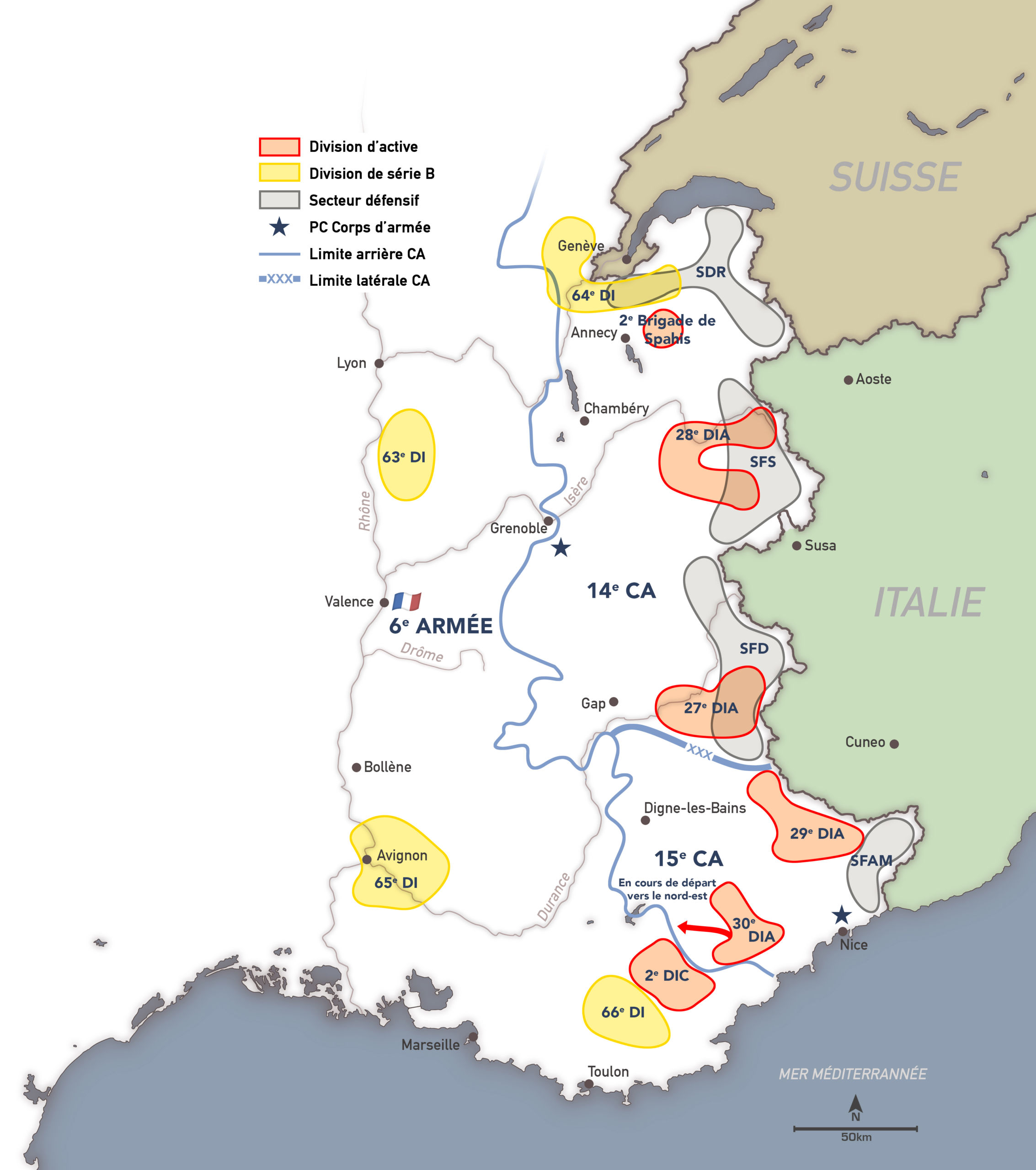

At the end of September, when it became certain that Italy would remain in a holding pattern, the General Headquarters (GQG), which was short of troops for the north-eastern front, began to draw on this theater of operations. The TOSE and the 6th army were merged. General Billotte was appointed head of Army Group No. 1 (AG No. 1). The 16th Army Corps (CA) staff left in early October. Then it was General Besson's turn to be called to command AG No. 3 on 22 October. He was replaced by General Olry, who had previously commanded the 15th Corps, responsible for defending the Alpes-Maritimes. At the same time, the five excellent active alpine infantry divisions (more than 22,000 men each) and the A series (16,000 men, of which about 30 percent were active), left the southeast. General Olry only had two army corps (14th and 15th), which included the Rhône defensive sector, three fortified sectors (Savoie, Dauphine and Alpes-Maritimes), three series B infantry divisions (from north to south, the 66th, 64th and 65th IDs) and an incomplete colonial infantry division (the 8th DIC), i.e. 190,000 men, of which 85,000 were combatants.

At the beginning of December, the staff of the 6th army, which came under the orders of General Touchon, was sent to Burgundy, to Gevrey-Chambertin to be precise, as a reserve for the GQG. In fact, 257 officers out of the 300 at the Valence headquarters left the region. General Olry had to organize himself with the remainder, which was then called the HQ of the Alps Army. No doubt the GQG did not want to give a number to this army, as it could not provide it with all the support units normally provided for in the manpower tables of a standard army.

Moreover, it must be noted... the potential front in the southeast was of little concern to the high command during the entire phony war.

However, in return for the little interest he showed in him, the GQG gave General Olry a wide margin of initiative, which the latter did not deny himself. As a central figure, his character and training had a decisive influence on the operations.

The phony war

It is possible to distinguish two « periods » during this phony war which will last in the Alps until June 10, 1940. The first, characterized by an extremely harsh winter, lasted from September 1939 until the end of April, then the second, which began on May 1, and was marked by four characteristic phases of ten days each.

The winter period

We have seen that since the end of October, the 6th Army, which became the Army of the Alps at the beginning of December, had only a few troops, including the three infantry divisions, which were poorly equipped and composed almost exclusively of reservists, many of whom had done their military service in the 1920s or early 1930s.

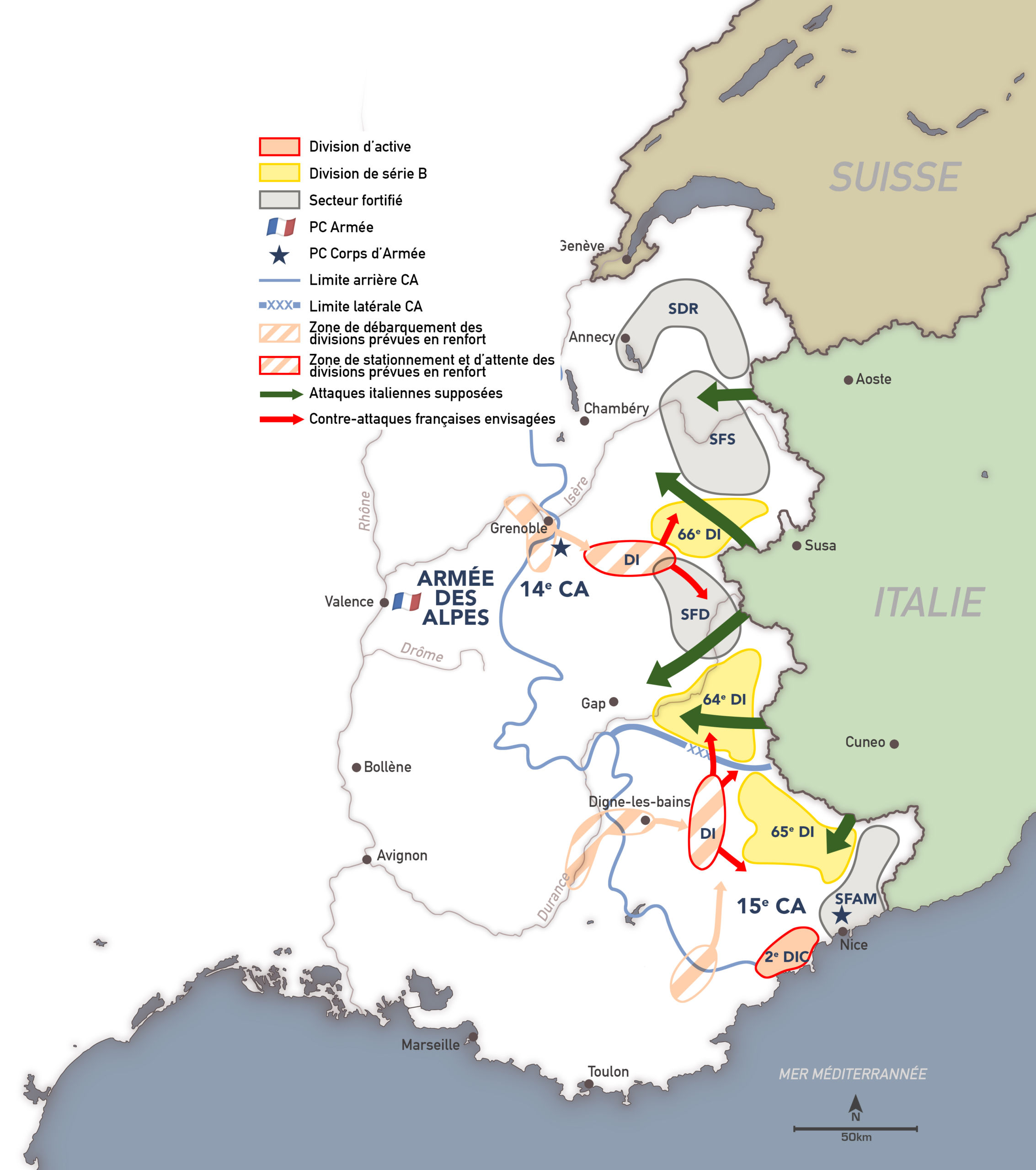

General Olry worked very hard to improve their potential and to make them capable of waging a defensive battle from the spring onwards. For there was no longer any question of an offensive in Italy, as some French studies had predicted before the war. The fighting would have to take place near the border, on an organized line, with outposts and sections of scout-skiers (SES) that would slow down the enemy, who would be methodically shelled by artillery, before they came up against the main line of resistance.

Olry has been thinking about the defense of the Alps for 8 years. He is convinced of the accuracy of his analysis and has no difficulty in sharing it.

To achieve his goal, he had to forge the combat tool he felt he needed. First of all, and this was a priority, he had individual and collective training resumed. As the winter prevented the Italians from going on the offensive, the commander of the Alpine army brought the divisions down to the valleys where they could live and learn more easily. He decided to create training centers for all the specialists (transmitters, collective weapons, etc.). In doing so, he was fortunate to have qualified instructors from the SES and four mountain artillery regiments that the GQG had agreed to leave in the Alps or to exchange when the five Alpine divisions left for the northeast. In order to be sure that he was being perfectly obeyed, General Olry often sent his chief of staff, General Mer, to check on the functioning of the training centers. The aim was to avoid routine or even hibernation in the units and, on the contrary, to maintain vigor, discipline and morale. It should be noted that in the archives of the Service historique de la Défense, there is no trace of requests for the creation of these centers at the GQG.

The commander of the Alpine Army takes his responsibilities and acts in a completely autonomous way.

General Olry also set out to perfect the main line of resistance, as long as the temperatures allowed work to continue in the high mountains. He also planned from the outset to ensure its defense in depth: a second position based on pre-prepared destructions should make it possible to delay the enemy if he managed to break through the main line of resistance.

Finally, he organized the command on the front by sectors and valleys, so that each local commander would have at his disposal both mobile troops from the infantry divisions and fortress troops from the fortified sectors. The use of artillery was studied in great detail, so much so that some batteries were sometimes split up to defend a dangerous axis.

April was the month of the resumption of the system at the border, both in Italy, where the troops had been brought back to the valleys, and in France. General Olry issued directives to this effect during the second half of March.

The order of operation, the war plan, was sent to the army corps on April 19. The latter had 10 days to indicate the manoeuvre they intended to adopt before carrying it out in early May. It should be remembered that Italy was still a non-belligerent country. However, General Olry, in all the orders he gave, acted as if war was going to break out in the following days.

He has received no guidance or direction from above, but places his army under stress, ready to act, based on what he imagines and on the intelligence he gathers daily.

It should be noted that the first Italian directives in preparation for the entry into the war only date from March 31, 1940. From April onwards, the transalpine troops were gradually deployed in large numbers near the border. These movements, observed by the French intelligence service, led General Olry to become certain that the Italians would soon enter the war.

Max Schiavon

Photo : fonds Raymond Bertrand

Max Schiavon

Max Schiavon (préf. François Cochet), Victoire sur les Alpes : juin 1940, Briançonnais, Queyras, Ubaye, Turquant Parçay-sur-Vienne, Mens sana Anovi, 2011, 475 p. (ISBN 979-1-090-44706-6).

Frédéric le Moal et Max Schiavon, Juin 1940, la guerre des Alpes : enjeux et stratégies, Paris, Economica, coll. «Campagnes & stratégies. / Grandes batailles » (no 83), 2010, 488 p. (ISBN 978-2-717-85846-4).

(fr) David Zambon, « L’heure des décisions irrévocables : 10 juin 1940, l’Italie entre en guerre », in Histoire(s) de la Dernière Guerre, no 5, mai 2010.

Giorgio Rochat (trad. Anne Pilloud), « La campagne italienne de juin 1940 dans les Alpes occidentales », Revue historique des armées, no 250, 15 mars 2008, p. 77–84 (ISSN 0035-3299, lire en ligne [archive], consulté le 26 mars 2020).

Richard Carrier, « Réflexions sur l’efficacité militaire de l’armée des Alpes, 10-25 juin 1940 », Revue historique des armées, no 250, 15 mars 2008, p. 85–93 (ISSN 0035-3299, lire en ligne [archive], consulté le 26 mars 2020).

Max Schiavon, Une victoire dans la défaite, la destruction du Chaberton, Briançon 1940, Parçay-sur-Vienne, Anovi, 2007, 266 p. (ISBN 978-2-914-81818-6)

Bernard Cima, Raymond Cima et Michel Truttmann, La glorieuse défense du Pont Saint-Louis : Côte d’Azur, ligne Maginot : 1940, Menton, R. Cima, coll. « SFAM ligne Maginot. » (no 2 ; 1), 1995, 23 p. (ISBN 978-2-950-85052-2, lire en ligne [archive]) [PDF]

Pallière, « Les combats de juin 1940 en Savoie : le déferlement des Allemands », dans Mémoires et documents de la Société savoisienne d’histoire et d’archéologie, Société savoisienne d’histoire et d’archéologie, coll. « L’histoire en Savoie » (no 94), juin 1989, 56 p. (ISSN 0046-7510)

Général E. Plan et E. Lefevre, La bataille des Alpes. 10-25 juin 1940. L’armée invaincue., Paris, Lavauzelle, 1982, 175 p., in-4

Robert Dufourg, La bataille des Alpes (Juin 1940) (brochure), Bordeaux, Taffard, imprimeur, 1953 (lire en ligne [archive])

Général Mer, La bataille des Alpes 1940 : Conférence faite au Grand Cercle d’Aix-les-Bains, Aix-les-Bains, Comité du Souvenir français d’Aix-les-Bains, 9 septembre 1945, 41 p., brochure (lire en ligne [archive])