Dès le 20 mai, avec une grande intelligence de la situation, Olry diffuse ses premières directives pour mettre en état de défense la zone arrière de son armée.

He specified his idea of maneuver after June 12: he wanted to create new lines of defense facing north and west, to prepare obstacles, in particular by blowing up bridges, and to place command troops mainly behind the cuts. In this context, he ordered to open all the valves of the dams. The flow of the Isère, already in flood, reached 1,100 m3 per second instead of the normal 500 m3. The river became impassable by makeshift means, notably with rubber dinghies.

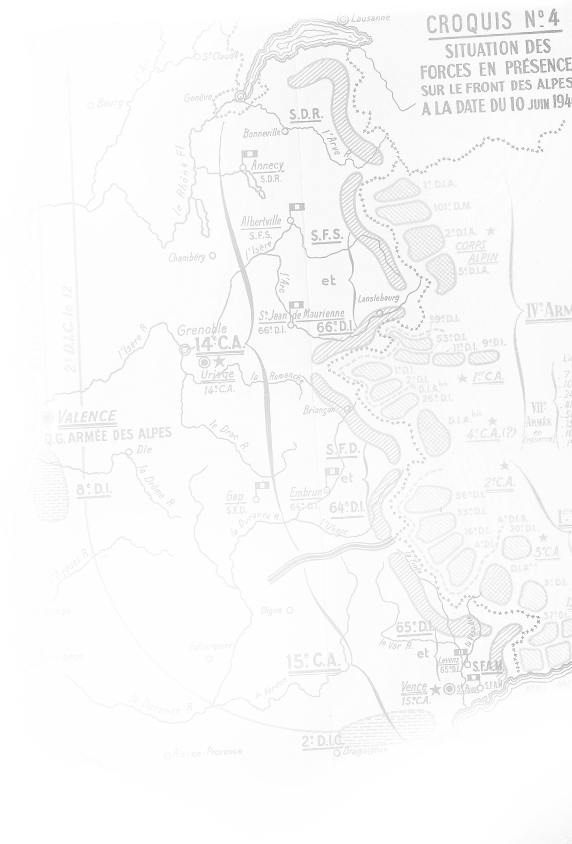

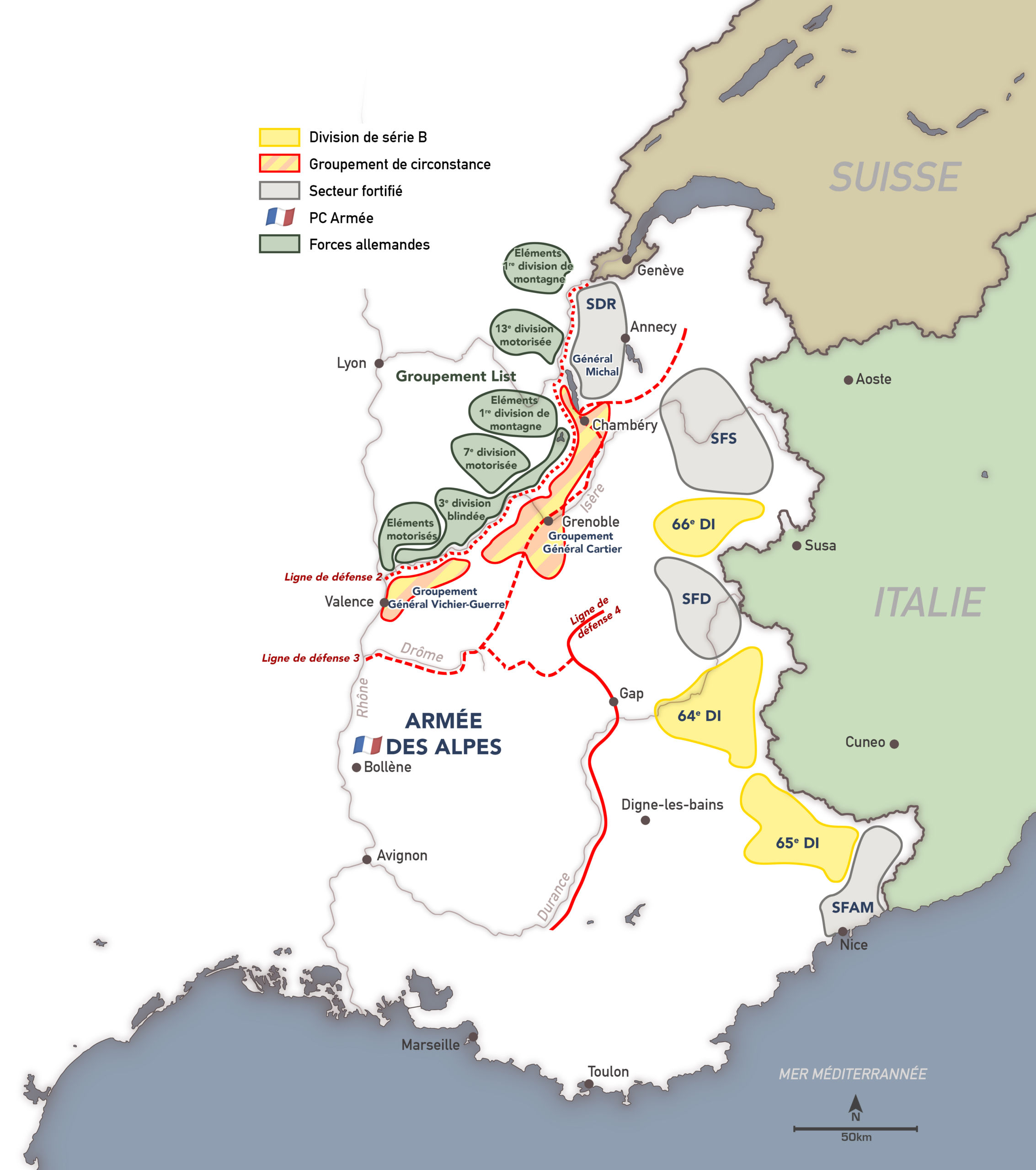

The principle adopted was not to take any units that were facing the Italians. In concrete terms, General Olry decided to create new marching units from the depots. He planned to set up not one but three successive lines of defence in the short term, which would allow for retreats and stoppages, even if the enemy managed to break through at a given point. The first line of defense was located on the Rhône, from Lyon to Bellegarde. The second was on the Isère river, extended by the Chartreuse massif. Finally, the third line was marked out by the Durance and the Vercors.

As soon as his decision was made,

le commandant de l’armée convoque tous ses chefs de bureau, ainsi que ceux des 14e, 15e et 16e régions, et donne ses ordres. La mise en place du dispositif face aux Allemands devient prioritaire.

To organize and command the marching groups he was creating, General Olry needed very energetic leaders

In order to organize and command the marching groups he was creating, General Olry needed very energetic leaders who knew how to make decisions quickly and who had strong authority, especially with regard to heterogeneous troops who had little time to get into place. Without worrying about the GQG, which was in fact away from home and difficult to reach, he recalled from retirement General Vichier-Guerre, who was given the mission of stopping the Germans east of Valence, and also called on General Cartier, a renowned alpine who was known throughout the army for his very demanding and tempestuous character. He commanded the Chartreuse-Rhône sector, which protected Chambéry and Grenoble. Finally, wanting to be sure of his distant rear, he recalled General Grandjean, who took command of the 15th region in Marseille.

From June 14, the roads of the Rhone Valley began to see long columns of refugees, both military and civilian, flowing in.

These were often units from the services of army group 2 (which, relying on the Maginot line, defended Alsace-Lorraine), and men from the air bases who were fleeing in a more or less orderly fashion, without knowing exactly where to go.

The new marching units were created by the 1st office of the Alps army in the depots of the 14th and especially the 15th regions, mainly by recovering men who were flowing back into the Rhone valley, and with the thousands of volunteers of all ranks who were waiting in the ports to join the Levant or North Africa. The Air Force and the French Navy also provided formed units.

In addition to the existing depots, three « organization centers » (sic) were created with the aim of setting up, from units and equipment of all origins, new troops capable of going on line. The Cavalry had its organization center in Orange, the Infantry and the Engineers in Avignon, the Artillery in Nîmes. The vehicle requisition commissions were re-established. Olry was given carte blanche, except for blowing up the roadblocks, a decision that would be taken by Weygand.

In the Rhone valley, tens of thousands of people, perhaps between 100,000 and 200,000, the vast majority of them civilians, advanced southwards on both banks of the river. After having this flow channeled on the right bank, the army commander organized an ingenious system. Three checkpoints were built, each commanded by an officer connected by telephone to the army headquarters. The first one is located at Tournon – Tain l'Hermitage. Here, the officer in charge simply observed the flow of refugees towards the South, and transmitted to the HQ in real time, the list of more or less formed units that he saw passing through, and which generally ranged from sections to companies. He indicated to Valence their strength, their armament and the vehicles they had. The first army office took note, had a few minutes to decide, and then telephoned its orders to the officer in charge of the second roadblock, located eighteen kilometers further south, in Saint-Péray. Thus, when the unit spotted in Tournon arrived at the second roadblock, the officer in charge directed it to its final or temporary destination.

Three cases may arise. Either the unit is judged totally unfit for combat and in this case, its equipment (mainly weapons and vehicles) is recovered and the men are left free to continue their way to the South on foot. Either it is judged usable in the long term, and it is then directed towards an organization center. Or it is judged capable of resuming the fight immediately, and in this case it crosses the Rhone to join the sector it will have to defend. All along the way, the gendarmes and the liaison officers made sure that everyone followed the path that had been set for them. A final roadblock was set up at Pont-Saint-Esprit, because the command hoped to be able to recover a few new units that had arrived there via transverse roads.

In the organization centers, as soon as a unit was deemed operational, an officer from the 1st office came to inspect it, and if he confirmed the opinion of the center chief, the 3rd office of the army took it into account, while the 4th office provided for its transport to the front and then its daily supply. In this period, the main difficulty was to find enough officers of value to command these marching units.

In the end, all of these measures made it possible to recover and set up the value of three light infantry divisions, a total of 22,280 combatants. The result obtained exceeded all expectations.

One last element perfectly illustrates General Olry's ability to project himself into the future. On June 21, he sent his subordinates a secret personal instruction (IPS). The commander of the army of the Alps explained how he saw the situation and gave his orders. His army, which was static, was placed in a position facing due east, opposite Italy, and had to remain there despite the German danger that was emerging. To oppose the latter, he will mainly use the marching units that he has set up. Then he continued his instruction with these words, which were very meaningful:

The defeat of the North-East that we are facing is not ours. With regard to Italy, which is our normal adversary, which we contain at 1 against 4, I want us to keep our front high.

Personal and Secret Instruction of General Olry, June 21, 1940He told his units that if they were surrounded by the Italians and Germans, they would have to surrender to them, because he did not want the Italians, whom he considered to be beaten, to take the glory for themselves at a lower cost. In the poisonous atmosphere of the end of June 1940, he wanted the soldiers of the Alpine army to know that they had fulfilled their mission, a guarantee of hope for the future.

What happened next is well known. At the time of the armistice, the Italians had managed to approach the French resistance position in only a few places, having suffered very heavy losses. Faced with the Germans, General Olry succeeded in extremis in keeping his line of resistance on the Rhône and Isère rivers. Despite final attempts in the days preceding the armistice, the Wehrmacht was unable to enter Grenoble.

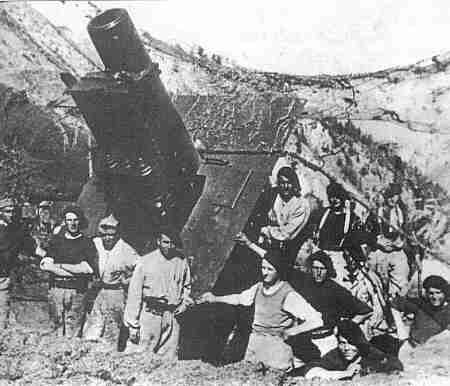

Photo : @cedricmas

Max Schiavon (préf. François Cochet), Victoire sur les Alpes : juin 1940, Briançonnais, Queyras, Ubaye, Turquant Parçay-sur-Vienne, Mens sana Anovi, 2011, 475 p. (ISBN 979-1-090-44706-6).

Frédéric le Moal et Max Schiavon, Juin 1940, la guerre des Alpes : enjeux et stratégies, Paris, Economica, coll. «Campagnes & stratégies. / Grandes batailles » (no 83), 2010, 488 p. (ISBN 978-2-717-85846-4).

(fr) David Zambon, « L’heure des décisions irrévocables : 10 juin 1940, l’Italie entre en guerre », in Histoire(s) de la Dernière Guerre, no 5, mai 2010.

Giorgio Rochat (trad. Anne Pilloud), « La campagne italienne de juin 1940 dans les Alpes occidentales », Revue historique des armées, no 250, 15 mars 2008, p. 77–84 (ISSN 0035-3299, lire en ligne [archive], consulté le 26 mars 2020).

Richard Carrier, « Réflexions sur l’efficacité militaire de l’armée des Alpes, 10-25 juin 1940 », Revue historique des armées, no 250, 15 mars 2008, p. 85–93 (ISSN 0035-3299, lire en ligne [archive], consulté le 26 mars 2020).

Max Schiavon, Une victoire dans la défaite, la destruction du Chaberton, Briançon 1940, Parçay-sur-Vienne, Anovi, 2007, 266 p. (ISBN 978-2-914-81818-6)

Bernard Cima, Raymond Cima et Michel Truttmann, La glorieuse défense du Pont Saint-Louis : Côte d’Azur, ligne Maginot : 1940, Menton, R. Cima, coll. « SFAM ligne Maginot. » (no 2 ; 1), 1995, 23 p. (ISBN 978-2-950-85052-2, lire en ligne [archive]) [PDF]

Pallière, « Les combats de juin 1940 en Savoie : le déferlement des Allemands », dans Mémoires et documents de la Société savoisienne d’histoire et d’archéologie, Société savoisienne d’histoire et d’archéologie, coll. « L’histoire en Savoie » (no 94), juin 1989, 56 p. (ISSN 0046-7510)

Général E. Plan et E. Lefevre, La bataille des Alpes. 10-25 juin 1940. L’armée invaincue., Paris, Lavauzelle, 1982, 175 p., in-4

Robert Dufourg, La bataille des Alpes (Juin 1940) (brochure), Bordeaux, Taffard, imprimeur, 1953 (lire en ligne [archive])

Général Mer, La bataille des Alpes 1940 : Conférence faite au Grand Cercle d’Aix-les-Bains, Aix-les-Bains, Comité du Souvenir français d’Aix-les-Bains, 9 septembre 1945, 41 p., brochure (lire en ligne [archive])